In Korean classrooms, multiracial students struggle to fit in

But even after spending more than six months learning Korean at an alternative school, going to school is still torturous. He was recently admitted to a public school near his home, but soon decided to quit.

It is almost impossible for him to follow the class or make friends, said Kim Ji-sun, a consultant from Seoul On Dream Multicultural Education center, where he learned Korean.

“His teacher told me that he always sits alone and hardly speaks to anyone,” she told The Korea Herald, noting that the boy is now only waiting to come back to the alternative school.

|

| Children from China, Thailand and the Philippines attend a home-schooling program run by the Global Sarang School in Seoul. (Yonhap News) |

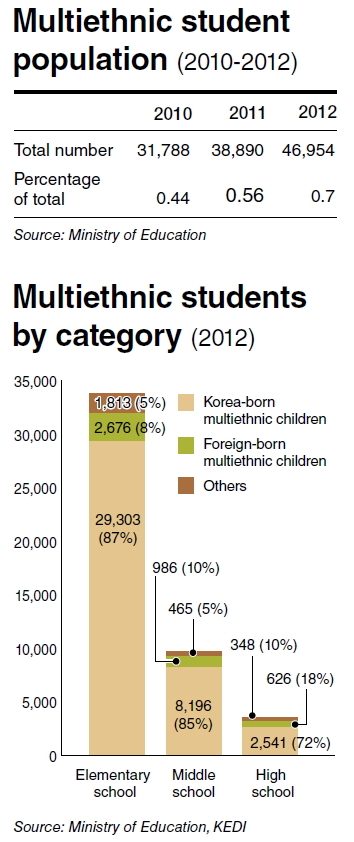

Korea is rapidly becoming a multicultural society, with the increase in ethnic and cultural diversity already reflected in classrooms. Data puts the current number of multicultural primary and secondary school students in the country at near 48,000, more than double what it was three years ago.

It appears, however, many of them find it hard to fit into classrooms here. According to government data, more than 200 students from multicultural families dropped out of school from 2010-2011 due to difficulties adapting.

Student dropouts are nothing new, but there seems to be a genuine problem with the current education system which turns away, especially, multiethnic students.

Until recently, the multicultural children were mostly born in Korea from foreign women married to Koreans. Today, an increasing number of children are brought here from overseas following parents’ divorce, remarriage and immigration.

The language barrier is the major concern, especially for foreign-born multiethnic children, according to Ryu Bang-ran, a senior researcher from the Korea Education Development Institute.

Data from the Ministry of Justice shows that there are more than 6,000 foreign-born children of school age here, nearly twice as many as a year ago. Nearly 83 percent, or 4,800, are from China.

“The problem is most of them came here with little or basic Korean language skills, so it makes hard for them to go to school,” Ryu said.

In research, the problem is also apparent. A survey of 413 newly immigrated children in Gyeonggi Province found that about one-third of them cited learning the language to be the most difficult part of living in Korea, followed by adjusting to the new environment and making friends.

There is no official data available regarding school-age children outside of the public education system, but Ryu estimated that more than 6,100 multiethnic children are currently not in school, indicating that the government has been slow to meet the needs of those children.

Ryu suggested that the country should learn from the U.S., which has a long history of dealing with immigration.

In the U.S., English as a Second Language programs have long been in public education systems due the large influx of foreign-born children. Currently ESL programs are in place at all public schools from pre-kindergarten to high schools.

“We should encourage schools to develop Korean as a Second Language curriculum to teach foreign-born multiethnic students,” Ryu said.

The dilemma is, she added, it is difficult to introduce KSL in schools as only a small number of children are non-native Korean speakers.

“Also, schools here are reluctant to take the leading role, because they acknowledge that the more multiethnic children there are, the more work there is to handle,” she added, suggesting the government needs to solve the dilemma

In fact, KSL programs are being developed. The government announced last year that, starting this year, it would introduce the Korean language classes for newly admitted multiethnic children, allowing them to acquire a the level of Korean necessary to adjust to the regular school curriculum.

The plan, however, has been at a standstill amid the government transition since the presidential election.

To successfully benefit the non-native multicultural students, the Education Ministry should provide more trained teachers, according to Hong Jong-myung, a linguistics professor at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies.

“Currently, teachers receive only short training to run the KSL program. But in the long term it is important to nurture teachers specialized in teaching Korean as a second language,” added Hong, who also heads the Seoul On Dream Multicultural Education Center.

The government has announced that it would increase the number of preparatory schools, where children can take basic language and culture classes before entering regular school.

There are currently 26 preparatory schools for multiethnic children around the country, each with a quota of around 60-90 students.

Although the government is planning to add 24 schools by end of this year, they are still significantly insufficient to meet the growing needs of multiethnic children.

In Seoul, for instance, there are 1,219 non-Korean children, but only 68 of them had been admitted to preparatory school as of April 2012.

Some believe building more alternative schools that use a nontraditional curriculum designed for multicultural children can be one solution. There are currently four alternative schools, one primary and three secondary schools.

“But alternative school can’t be a solution for all multiethnic children,” Ryu added, “It can also be disadvantage for them, because once they learn from the alternative schools, they can’t adapt to other public education.”

While the authorities have been slow to come up with ideas to help multiethnic children adapt here, like the 15-year-old boy, many of them are in despair, wondering about their future.

A survey of 1,275 multicultural students around the country showed that the majority of them answered they had “no idea” to the question about future education and career desire.

“The multiethnic children are suffering in our education system because their unique needs are not being met,” said Yoon Seok-ryong, the principal of Masongjungang Elementary School in Gimpo, Gyeonggi Province, where about 10 percent of students are from multicultural families.

Yoon noted he believes multiethnic content must be integrated into the overall classroom curriculum.

“We have many multicultural students, so we make sure every curriculum, even pictures on the wall, reflect these children,” he said.

“We also work very closely with their families, and invite them to teach their language and culture to other students. It really helps students understand each other.”

He acknowledged, however, he feels more teacher training programs are urgent to support the children.

“Many teachers still lack the understanding of these students, and don’t like to teach them as it might mean extra work. Teachers must understand that they are also part our society,” he added.

Source: The Korean Herald by Oh Kyu-wook (596story@heraldcorp.com)